10

The Chef And The Guide

“What the Hell was wrong with you last night?” asked Andrew, emerging from the McLintock house at a somewhat advanced hour of the morning to find Aidan sitting on the deck that gave a view of the lake, hurling pieces of McLintock decorative stone into the water.

“Nothing,” said Aidan with a scowl, hurling another carefully placed oval stone at the lake.

“Those aren’t just odd rocks, you birk, they’re decorative garden stones, carefully graded and acquired from a garden centre at a specified and not cheap price per stone,” said Andrew heavily.

“What?” replied Aidan crossly.

Andrew sighed. “You got a firm to do that bloody garden of yours in Sydney, didn’t you?”

“Yes. Well, left it to Paulette, but you’re correct in essence.” He looked dubiously at the remaining stones. There were quite a few of them: the deck, unremarkable in itself, had a nasty sort of er, trough, or, er, trough, really, running along its edge filled with them. About a hand’s span wide. Could it be for drainage? But there were narrow spaces between each board, surely— “Okay, I’ll buy it: it was a joke, wasn’t it? They don’t charge by the piece for bloody stones, even these days.”

“No, it wasn’t, and yes, they do for stones that size, otherwise possibly by weight, though I have seen them for sale by metric capacity.”

Aidan looked blank for a moment and then his face lit up. “By the litre? That’s how they sell cockles in France!”

“Yes, well, in less civilised climes it’s how they sell ruddy garden stones, and before you ask, that row of them is functionless. Goes with that other row of them down on the lawn next to that double row of mondo grass.”

“Eh?”

“Those horrid blackish clumps all in a row, have you been blind as well as deaf to everything that’s happened in the last twenty years?” said Andrew loudly.

“Ssh, you’ll wake the sleeping beauties! Well, yes, obviously, must’ve been. Did you say that black stuff’s grass?”

“Oh, shut up, Aidan,” said Andrew tiredly.

Aidan shrugged but shut up.

“Um, ’tisn’t surprising that Bobby didn’t want to come out for the funeral, Aidan,” ventured his friend after quite some time.

“Mm? No, never thought he would,” said Aidan, suddenly smiling at him. “He’s never been a hypocrite. But at least he’s agreed to take his share of the bloody estate. Well, saw my point that we all loathed the old bastard so we might as well divvy it up equally. And Jerry’s a sensible chap: he pointed out that they could throw large chunks of it away on something that bloody Dad wouldn’t have approved of!”

He hadn’t mentioned that before, though Andrew already knew that Bobby had agreed to accept an equal share of the inheritance. “Like what?” he said weakly.

Aidan smiled. “Anything! No, well, they’ve always wanted to do a tour of Japan really slowly, seeing the old traditional way of life. Bathhouses, sleeping on futons on the floors of tiny inns, that kind of thing. Then there’s the Machu Picchu trek: this’ll mean they’ll be able to afford it before they retire and while they’re still fit enough to take the altitude. And they have been to Europe several times, but a summer on canal boats was definitely mentioned!”

“Right,” agreed Andrew, grinning, though reflecting there were was nothing objectionable in any of these projects but that Sir Simon Vine had always been a joyless old prick, he probably wouldn't have approved. He hesitated and then said lightly: “So what are you chucking your share away on?”

There was a long silence and Andrew began to wish he hadn’t asked. Then Aidan shrugged and said: “Oxfam.”

“What?” said Andrew weakly.

“You heard.”

“Buh— All of it?”

“Yes. No-one in the family needs it, though I’m quite sure Fenella and Aprylle would be happy to spend it on their backs.”

These were his daughters—the names of course had been Paulette’s choice. Wincing slightly, Andrew nodded. “Any sign of a grandchild, yet?”

Fenella had been married a year back at the age of just twenty-one to a highly suitable young lawyer from the firm. In her father’s expressed opinion she’d done it as an alternative to getting a job after she’d finished her indifferent B.A. –She was quite bright, had never had to put any effort into passing her subjects, and apparently had never wanted to excel at them.

“No, Andrew,” said Aidan sweetly: “being a stay-at-home wife has nothing whatsoever to do with procreation in the twenty-first century. It’s purely a matter of economics.”

“Right,” he said feebly. “And Aprylle?”

“The modelling career didn’t result in a Scandinavian prince so she’s given it up. Ya want more?” he said drily.

Swallowing, Andrew replied: “Well, yes. What is she doing?”

Aprylle was the same age as Andrew’s Bruce. Drily Aidan returned: “Nothing as sensible as agricultural science, I can promise you! Advanced fabric art.”

“Eh?”

“Yeah. She did some art at school and apparently that and her academic marks got her into this diploma course. –Or possibly her mother offered the college a large donation, I have no idea.”

“Is it an accredited course?” he asked feebly.

“I have no idea, Andrew,” replied Aidan politely.

“Right,” he said feebly. “I remember her as a merry little grig,” he added feebly. “Plumpish and a mop of black curls.”

“So do I,” said her father tightly. “Two years back she was so painfully thin I thought I’d have to get her into a specialist clinic—not anorexia, bulimia, used to shove her fingers down her throat after dinner—but the flesh started to come back with the disappearance of the modelling career, so it can’t have been clinical bulimia, only galloping stupidity. The latest is the Goth look.” Andrew just looked blank so he elaborated: “Think we might have called it Punk. Black lipstick, white face, studded dog-collar, large safety-pins dangling from the platinum ear hoops she got for her fifteenth birthday, black leather and chains. At least so far she’s spared the world the nose stud and tongue stud, evidently the modelling agency advised against them, but there’s one in the navel.”

“Uh—right,” he agreed, wincing. “With fabric art?”

“It’s not lovely handmade quilts, old man, it’s advanced fabric art,” said Aidan with a smile in his voice.

Andrew replied with some relief: “Oh, right! Bulgy life-size stuffed mannequins, then?”

“That’s part of it, though rather old hat these days. But I don’t think she attempts to reconcile ’em.”

“No!” he agreed, shaking slightly. “Um, so what was up last night?’

“I said: nothing,” said Aidan with a sigh.

“I thought the food was lovely,” said Andrew on a defiant note.

“On its level, yes.”

“Aidan, for Chrissakes, this is the backblocks! If you want fancy gourmet muck in strange little piles, try that Fern Gully place. Wal categorised it feelingly as ‘poncy as all get out’, so I’d say it’s right up your alley!”

“I don’t want fancy gourmet muck in strange little piles, thanks.”

Sighing, Andrew said: “All right, I give in. What was wrong with that rabbit?”

Aidan’s long, rather sardonic mouth twitched a little. “Don’t say you didn’t ask for it. Number one, she’d used domestic rabbit, not wild, and my guess’d be those frozen Chinese ones. Factory-farmed. Wild rabbit is much gamier. Or, put it another way, tastes like meat. Number two, more Marsala and more garlic would definitely have improved that dish, as would long, slow stewing in a sealed casserole dish in, preferably, a wood oven.”—He ignored Andrew’s deep indrawn breath.—“Number three, although those runner beans were a pleasant side dish, and not overcooked, the rabbit screamed out for oven-baked eggplants and capsicums done in a good olive oil. I’d even have accepted the odd slice of potato done with ’em, too. That brown rice was bloody boring.”

“Well, thanks for that. Why don’t you open a real Italian restaurant like that bloke in Australia you were telling us about last night? Dunno that Taupo could provide the paddle-steamers to drop off the customers, but I dare say your parking lot could hold both cars,” he ended airily.

“Yeah, very funny,” admitted Aidan with a silly grin. “Unfortunately there’d be about that number of customers, judging by the crowds in those ghastly dumps we tried in Auckland with their fancy gourmet muck in strange little piles.”

“Mm. Well, offer your services to Jan—take over from her. Or, no, tell you what! Livia needs a cook!” He collapsed in horrible sniggers.

“Yeah, hah, hah.” Aidan stood up. “Want coffee?”

Andrew wiped his eyes. “Only if it’s genuine Italian-style made in that genuine Italian-style coffee-pot you scoured the Auckland kitchen shops for.”

“It is,” he said briefly, striding away.

Andrew made a face at the lake. “It wasn’t the food, domestic rabbit or not,” he noted drily.

Of course Andrew’s suggestion about running a restaurant and his even less serious one about becoming a cook were ridiculous and Aidan wouldn’t have given either idea even a passing thought had it not been for a combination of circumstances which was purely coincidental.

In the first instance, though it was a minor point, Don Harrison was very relieved to be offered real coffee and praised his brew to the skies, noting that it was the first actual coffee he’d tasted over here. In the second place Candy not only agreed with him—she usually agreed with him, it certainly made for marital harmony, if not anything approaching variety or spice—but into the bargain showed Aidan two of her own tricks with coffee. The results were the best café au lait he’d had since he was last in France—complete with the grand bol, Candy found some white ones that were almost exactly the right size in one of the white Melamine cupboards—and the most ambrosial brew flavoured with eau de fleurs d’oranger! Okay, she’d found it in a supermarket not far from Dad’s place, he’d take her word for it. Though her admission that she’d been astounded to find it was easier to credit. Where the Hell had she picked up— Right. Done a cookery class that was taken by a Lebanese woman. Most of their cooking was very, very time-consuming, suited to housefuls of women who were at home all day and didn’t mind grinding and mincing stuff and stuffing tiny things and making tiny rolls of this and that, but there were one or two dishes she’d been able to use, plus the coffee idea! Don loved it. Not for breakfast, of course, but perhaps in the afternoon, with a lovely crescent-shaped biscuit? She offered eagerly to make the biscuits, so Aidan let her, though privately sure they wouldn’t be a patch on those from the little Lebanese bakery he patronised in Sydney. They were indistinguishable from them. Dusted with icing sugar an’ all. No wonder Don was so stout!

The third factor was Libby’s reaction to his phone call. Not her immediate reaction, no. He’d hesitated for some time before making the call, though he wasn’t kidding himself that he didn’t want her. That simple jersey-knit navy top she’d worn the other night, though not as designedly seductive as the camisole over the turquoise bra, had been a real turn-on. And in fact the simpler style suited her much better. He did realise he’d managed to get up her nose again, though he wasn’t sure exactly what he’d said to annoy. Uh—criticised the white wine? But the restaurant wasn’t responsible for its shortcomings, the vineyard was. He was blissfully unaware that she’d overheard his comment on the salmon mousse. And, though not unaware that she’d resented his reaction to the puddings or lack thereof, didn’t realise just how offensive she’d found him. The more so as by that time his own feelings had been ruffled by her failure to so much as smile at him, let alone indicate that she, uh, well, looked on him as something more than a passing customer.

The first problem the phone call posed was finding her. He rang the ecolodge but she wasn’t there. Jan accepted his congratulations on the meal in a distinctly dry voice and explained that Libby, Jayne and Tamsin weren’t actually with them at the moment: they and her cousin’s daughter were staying on his side of the lake while the ecolodge was full. Yes, Libby did usually help with the waiting but she wouldn’t be working in the restaurant this lunchtime: she’d gone on an all-day trip to National Park to help Vern Reilly with a minibus load of their clients. Well, help with the picnic and the guiding, Aidan. Aidan said weakly he’d been under the impression she’d been living in Brisbane for the last forty years, to which Jan replied very drily indeed that she had but the “guiding” consisted of no more than pointing at things that old Vern had previously identified for her and making sure the twerps stayed on the track. And the help with the picnic consisted of unpacking the chillybins. To which Aidan replied limply: “What? Oh—yes. I’d forgotten you called them that here.” Thus enabling Jan to reply cordially that she’d forgotten what they called them in Australia and what was it, again? Aidan swallowed hard. He was ninety-nine percent sure she was taking the Mick. What they called them in Australia was “eskies,” the only possible derivation being a contraction of “Eskimo” and “bins.” Both pejorative and absurd—quite. He assured her cordially that she wasn't going to hear what they called them in Australia from his lips, at which Jan gave a startled yelp of laughter and admitted he’d had her, there. And she was afraid Libby didn’t have a mobile. They were due back about fourish, but knowing old Vern’s propensity for hiving off over the desert any time a client pointed at something that looked interesting, that could mean any time up until sevenish. Okay, he’d try later.

He tried later and got a voice that combined the very worst aspects of the female New Zealand accent—both high-pitched and nasal, plus the slurred short I that was endemic to the country—with the strong impression of a speaking prune. “Teeowpeeo Shores Uckolodge, thus us Jenut speaking, ken Oi hulp yeeow?” Approximately. He asked for Libby and got the information that she didn’t think she was back yet but she’d see. Aidan waited. Then the female came back on the line and said “Ken Oi ask who’s callung, please?” so he said very lightly: “Please tell her that it’s Aidan Vine and if she doesn’t want to speak to me I’m afraid I’m just going to go on calling.” Which elicited a gulp and the adjuration to hang on. Aidan held on for ages.

“Hullo?” said Libby’s voice breathlessly. “Sorry, I was having a shower!”

“What in?” replied Aidan languidly. “Thought the ecolodge was full?”

“It is! In Dad and Jan’s bathroom, of course!” she panted.

“Oh, right. Waiting tonight in that lovely blue outfit again, are you?”

“Yes. So what?” replied Libby suspiciously.

“Well, nothing, Libby, darling: just that I wish I was over there!”

“You need to book, it’s their busy season,” replied Libby grimly.

“I know. I’m sorry we didn’t manage to talk last night. And, er, I think we got off on the wrong foot somehow, didn’t we? I’m sorry. For everything, really. Well, uh, for whatever I might have said or done to upset you.”

Libby hadn’t expected him to offer any sort of apology, even one after passing remarks about the shower and her doing the waitressing, so she was very taken aback. “I was too busy to notice you. Did you want something?” she said gruffly.

“Yes, you!” said Aidan with a laugh in his voice..

He heard her swallow. Then she said in a weak voice: “No, it’s stupid.”

“Pooh! Just a little get-together for fun? ’Nother drive over to Rotorua, maybe? See the bits you liked without bloody Andrew dragging us off to gawp at large fish?”

“Jayne liked them. Um, no, I can’t, really, I promised Jan and Dad I’d be on deck.”

“Darling, you must have some free time, surely? What say I make a lovely lunch for you?”

“If this means you’ll make your sister make it, no.”

“No: if you come tomorrow they’ll all have gone off to Rotorua. Thought I might buy one of those famous organic chooks from that place next to you. They’ll be away all day and there’ll be just us, or just me and a large dish of poulet à l’estragon if you won’t come,” ended Aidan on a dry note.

“Jan makes that,” said Libby in a stunned voice. “It’s from a book that she calls The Greedy Cook.”

“Uh—oh! Good name for it! So is mine, though by this time I don’t need the book.”

“It’s a very old book, though. I mean, she bought it in about 1969!”

“Yes?” said Aidan politely. “I bought mine second-hand in about 1977 as a measure of desperation when Andrew and I were flatting together as students. His idea of cuisine was the original EnZed spag bog: a horrid mess of mince and over-boiled spaghetti. Still is, really! He didn’t realise that that rabbit last night, pleasant though it was, was the frozen domestic variety.”

Libby swallowed. “Jan said none of them would know. But Dad wouldn’t eat it.”

“I see!” said Aidan with a laugh. “It all becomes strangely clear, darling!”

“Um, yes. Um, well, he’s got standards as well,” she admitted.

“As well as whom, darling?”

“As well as you,” said Libby grimly. “That salmon thing, it was for all the middle-aged ladies in the floral frocks.”

“My sister is a middle-aged lady in a floral frock. Though I’m glad you realise I’ve got standards. Inconvenient though they can be,” said Aidan drily. “Well, will you come?”

Libby hadn’t intended to accept at all but somehow she found herself saying: “Um, well, yes. They don’t really need me at lunchtime, it’s more informal. Um, thanks.”

Not unnaturally Aidan was in a very good mood in the wake of this conversation and next morning got up very early, ate the last of the croissants which they’d brought down from Auckland with un grand bol de café au lait, left his sister a note which was shortly to astonish her, apologising for having taken the last two croissants and hoping they all had a lovely day, and took off for Taupo Organic Produce. As it was a choice of the Beamer which had belonged to his father, Andrew’s 4WD, or the large Volvo station-waggon which had also been his father’s and which Don had driven down, reporting that it drove like a tank, if a well engineered one, and it was a bugger remembering you had all that length and weight on behind, he took the Beamer. At the back of his mind he was aware that his cousin Caroline hadn’t come down entirely for Andrew’s company and that she would be considerably annoyed to find that he hadn’t been joking when he’d said the sulphurous tourist-laden atmosphere of Rotorua was all theirs; but as she’d foisted herself on them uninvited he didn’t give a damn. It was twenty-five years—more—since there’d been anything between them and if after two divorces and a very expensive period drying out in some clinic in California on what she’d screwed out of the second husband Caroline fancied there was, too bloody bad.

Taupo Organic Produce had a nice clean shop—he could see it must originally have been the sort of corrugated steel shed endemic to the EnZed pick-your-own facility, but it was now fully lined, and featured large folding doors at the front, already folded back at what was still an early hour—the Beamer had made very good time on the empty road into town. There was also a ceiling fan, not needed at the moment: the only one of its kind in the country, unless things had changed far more drastically than anything he’d seen since he’d been back had indicated. As well as a display of incredibly fresh-looking fruits and vegetables, which the people in charge were still putting out, there were ranks of glass-fronted fridges, and everything was spick and span and, well, clean. Aidan gave a deep sigh of which he was unconscious, and began to have a really good look…

He was admiring the herbs when the tall, dark-haired woman in smart cream slacks and fawn tailored blouse who seemed to be in charge came up to his elbow, greeted him politely by name and, reminding him that they’d met at Livia’s, expressed condolences on his father’s death. She looked so different that Aidan hadn’t recognised her: the outfit she’d been in at Livia’s dinner party had been bloody nearly as flashy as Livia’s own. He responded appropriately, trying frantically to remember her name, but she cut short his agony by saying: “Bettany Throgmorton.”

It hadn’t dawned on Aidan that it was her husband who was running this place. He was considerably taken aback. Bettany was an English actress mate of Livia’s, most definitely not out of the top drawer, though the voice was well modulated and very pleasant to listen to, but Hugh Throgmorton was a bloody retired British general! As haw-haw as they came.

“Do you need any help, Aidan? Those have just been picked and not all of the pickers can read very well, yet!”

Aidan smiled. There were several children in the shop, one of them serving a woman with some beautiful big tomatoes as they spoke. “That explains it, then!” The herbs were standing up in large plastic bins with water in them, and the names written on the front, but the contents didn’t all match the names: the thyme and the tarragon had been swapped.

“That’s the tarragon,” she said helpfully.

“Mm.” Aidan looked at the containers again. His lips twitched. They were in alphabetical order. “How very organised,” he murmured.

She laughed. “That’s Hugh: ex-Army, you see!”

“Mm. May I ask how long you’ve been out here, Bettany?”

“About two years. Hugh’s nephew married a local girl and—well, it’s a long story, but he decided to settle out here. I was staying with Livia and Wal: that’s how we met.”

“I see,” said Aidan, blinking a little and taking another look at the children. So they couldn’t be theirs. “This—uh—this must be a big change in lifestyle for Hugh.”

“Yes, but it’s giving him plenty of scope: the business was rather disorganised when he took it over, so he’s enjoying sorting it out. He’s no expert on the horticulture side, but he’s learning. And we both help in the gardens—there’s plenty of fresh air and exercise.” Her eyes twinkled. “In permaculture one doesn’t have fields,” she murmured.

Aidan didn’t get it but he smiled nicely and returned: “I see. It’s an attractive area, but isn’t it rather isolated in winter, Bettany?”

“It is very quiet, but Hugh’s a country boy: his family’s home is in the country. And we’ve made some nice friends: Jan and Pete from next-door, and Dan and Katy Jackson. And Livia and Wal, of course!” She shot him a shrewd look. “One does retire relatively young, in the Army,” she murmured. “‘Putting in his thirty,’ as they say.”

“Mm. Lucky Hugh,” said Aidan nicely. “Well, let’s see. The place I’m staying in has got tarragon: someone seems to have planted a herb garden at one stage and it’s self-seeded.”

“You’re lucky,” replied Bettany seriously. “It’s quite hard to establish. Well, you can buy them in bunches, like this, or the children are making up some mixed bunches.”

Aidan let her sell him a bunch each of thyme, marjoram, basil and rosemary, admitting that the McLintock garden also had loads of sage—the bunches were huge, but he could always dry them—and accepted a mixed bunch from a plump, round-faced little girl of about seven or so, not because he really wanted a warmish bunch of herbs that included several chive flowers and a marigold but because she was a such a funny little object. The organic poultry was so very tempting that he bought a couple of ducks as well as the chicken. And enough vegetables to feed a regiment, but they were just so fresh and tempting! The fruit, however, was a disappointment. Beautiful quality, but…

Bettany had left him to it while she served several other customers and helped the children finish putting stuff out, but now she came up to him again and said: “We’ve found that people like buying the berries in punnets, but they are all freshly picked.”

“Yes; I— Of course, it’s seasonal,” said Aidan lamely.

She hesitated. Then she said: “Yes. Apart from the early plums, Christmas plums, they call them, the stone fruit isn’t quite ripe yet, though our nectarines are almost ready. And one can’t grow the more tropical fruits here, or even very much citrus: the winters are too cold and the summers just aren’t hot enough. The fruiterers in the bigger cities offer more variety, and so do the big supermarkets, but at this time of year the apples will be cool-store ones, and of course bananas and pineapples are all imported, though I believe they are growing oranges in the far north where they don’t get the frosts. I found it very hard to adjust, after the huge variety one takes for granted in London!”

“Yes. I was planning a light tropical fruit salad… I suppose I was unconsciously expecting mangoes and pineapples,” said Aidan lamely. “And well, star fruit and… I must have completely adjusted to Australian conditions.”

“One would, yes,” she said kindly.

“No kiwifruit, even?” he said limply.

Bettany bit her lip, “Um, no, Aidan. We harvest them in May and June.”

The little girl had come up to them again. “I could get him some neckarines!”

“No, darling, the early ones are promised to that man in Auckland,” said Bettany firmly.

In that case it seemed to be a choice between berry fruit or melons. He didn’t mind rockmelon in fruit salad so long as there was fresh pineapple to counteract that rather cloying taste, but— No. He would buy some melons, they’d be nice for breakfast if nothing else, but for today’s lunch it’d be raspberries. The last of them? Well, he was in luck. Did they have cream? Gallons of it. And yoghurt. Did they make cheese? No: they used to, but Hugh had decided it wasn’t cost-effective.

Aidan and his carload of goodies departed with the expectable polite exchange with Bettany and an unexpected round ball of a garlic flower from the little girl.

Well, clearly Hugh Throgmorton had his work cut out for him there: Bettany had explained they supplied tree-ripened fruit; the logistics of getting it to the retail outlets must be a nightmare! And then there was the whole horticulture side of it: they produced such a variety of stuff. Though she had said that Hugh was rationalising that as much as was possible within the permaculture system. Evidently it went in for companion planting or some such and avoided huge fields of the one variety, which tended to encourage pests. No, well, presumably British generals retired with huge pensions: just as well, because in his opinion this sort of venture was highly unlikely to support even a halfway decent lifestyle: the man must be running it as little more than a hobby farm. Several people had mentioned the place to him, mainly at that dinner of Livia’s, but he’d been so preoccupied looking at Libby that he hadn’t taken much in. Um, started by some long-haired weirdoes that lived off the land and barely used actual cash money, wasn’t it? Not a sect, he didn’t think… Oh, yes: Jan Harper had said that permaculture in its pure form was a religion! Aidan smiled, but shook his head. The area was attractive, at least in summer, the results of the labour were beautiful, but—no. Not for him.

The chicken was simmering and he was whisking up a light batter for the zucchini flowers—over the top, yes, but he hadn’t been able to resist them: they’d just had a few, fresh-picked: Bettany had explained that most people didn’t know you could eat them—and Libby was due any minute and everything in the garden was lovely! Then a coy soprano voice that most certainly wasn’t Libby’s called: “Yoo-hoo! It’s only little me!”

Livia. Grimacing, Aidan went into the big living-room and out onto the deck: she would have come across the lawns. Uh—shit, something up? Livia looked distinctly dishevelled: a crumpled apron over a pair of faded pink cotton pirate pants she normally only wore when doing grubby jobs, the hair tied up in scarf, and the mascara which she was seldom without horribly streaked.

“Oh, Aidan, darling! It’s ridiculous, but I’m in a stupid fix!” she gasped.

Phew. At least it wasn’t Wal dropping in his tracks. “What is it?” he said limply. “Uh—come in.”

She allowed him to take her arm and usher her in. “Darling, what a wonderful smell! Is Candy in the kitchen?”

“No, she’s in Rotorua. What’s the matter, Livia?”

“I— But who’s cooking?”

“Me. What—is—the—matter?”

Grimacing, Livia admitted: “It’s the stupid microwave, darling. Well, no, it’s me, I suppose. Well, I don’t know what I did but it’s blitzed the lunch! Just some nice chicken pieces, and the book swore the microwave would do them, and I followed the instructions to the letter—”

Yeah, yeah. Oh, five women coming for a ladies’ lunch, eh? More fool her. He asked without hope where Wal was but the answer was gone fishing.

By this time they were in the kitchen and she gasped over the wonderful smell again and cried: “Darling, aren’t you clever! I never knew you were a cook!”

Aidan gave in. She and Wal had been very good to him when his father died—Wal had come over to Dad’s place and helped him through all the business of the funeral arrangements, in fact. Aidan hadn’t said he was a big boy and didn’t need any help, because he felt very strongly that he did. For one thing, he knew nothing whatsoever about the local funeral directors. And Livia had been a tower of strength, appointing herself in charge of the bloody phone that wouldn’t stop ringing and coping with the entire New Zealand legal Establishment and its hypocritical expressions of sorrow. Not to mention its bloody wives.

“All right, Livia: at immense cost to myself I’ll cook your lunch. Though your ladies aren’t getting the zucchini flowers.”

She threw up her hands and protested, of course, but gave in. She claimed to have all the basic ingredients for pastry, so he was considering quiche, when there was a knock at the French doors.

“That’ll be Libby and yes, you are ruining our date, but never mind,” said Aidan, going out to the living-room. “Hullo, darling, so that’s your boat!”

“Mm. Well, it’s a rental one. There wasn’t much choice, but it handles well.”

His eyes twinkled as he registered the full glories of the red, white and black launch but he said nicely: “Come on in. Slight change of plans: Livia’s had a culinary disaster, so I said I’d help her out.”

“Libby, darling!” cried Livia, bursting into the room. “It’s too dreadful of me, and I’m ruining your lovely lunch!” And blah, blah, blah…

Libby was very flushed—Aidan didn’t think it was on account of their date being spoiled, he thought it was on account of Livia finding out they had a date at all: hard to know whether to feel flattered or insulted, really! She was finally able to say: “Don’t be silly, of course we’ll help you out. I’ll come, too, Aidan, I can always chop things humbly like I do for Jan.”

“Right, let’s stir our stumps, then!” he said cheerfully. And with that they gathered up the lot, chicken and all—since his day was ruined he might as well go the whole hog and let them have it—and went over to the Tex-Mex horrors next-door. Where Libby, somewhat to his surprise, firmly dispatched Livia to change and do her make-up.

“Sorry about this,” he said with an awful grimace.

“Bullshit. They’re your friends,” replied Libby sturdily. “Hey, tell ya what! The ladies she’s invited are gonna be really surprised to get proper food!” she hissed.

This was the same woman who’d put him down because he’d merely wondered what was in the vol-au-vents at Livia’s frightful dinner party, but never mind, what with one thing and another Aidan was feeling so pleased with himself that he merely sniggered. And they got on with it.

Since Libby, giggling, discovered a whole selection of maids’ and cooks’ garments in a kitchen cupboard, they were able to do the thing really properly. Aidan in person, in a white double-breasted cotton cook’s jacket, opened the Marlborough Sauvignon Blanc for them and served the astonished ladies with their elegant little piles of courgette slivers in olive oil. –Vaguely remembered from a Jane Grigson cookbook: one of her few vegetable recipes not smothered in cream. Just sliced into quarter-inch wide sticks, dusted in flour and quick-fried. Libby then served the poulet à l’estragon with its side dishes of small new potatoes and small carrots au persil while Aidan opened another bottle for them. He didn’t think the ladies would appreciate a separate salad course so he didn’t bother with one and as Taupo Organic Produce didn’t sell cheese and Livia didn’t have any he simply followed it up with a mixed melon coupe—orange, pale green and pink, using his rockmelon and honeydew melon, with some of Livia’s giant watermelon—God knew what she’d been intending to do with it, it had been sitting in solitary splendour on the kitchen bench when they arrived—plus the one punnet of strawberries from Livia’s refrigerator, God knew what she’d been intending to do with ’em, the whole sprinkled lightly with castor sugar and—Aidan had had this mixture in Italy and he didn’t think the ladies would be taken aback by it—a little gin. Gordon’s, you got that faint taste of juniper coming through. Livia had melon scoops galore, so the end product was extremely artistic, so much so that Libby collapsed in giggles, suggesting a swirl. To which Aidan replied genially: “Geddouda here!”

Real coffee, almond wafers (Livia’s: bought in Auckland, he could only presume) and liqueurs in the sitting-room finished the feast and several of the ladies came through to the kitchen, not only to congratulate him fervently on the lunch but to enquire if he might be available for other bookings—?

Ignoring Libby’s gulp, Aidan explained smoothly that he was on holiday, this lunch was just a favour to Livia.

Oh, but surely he could manage just Mona—just Joan—just Diane? He took all their phone numbers, though warning them he didn’t think he could, and he and Libby were finally able to shove the dishes into Livia’s huge dishwasher, grab the pots and pans belonging to the McLintock house, and creep out. Avoiding the lawn in front of the sitting-room windows, yes.

“Phew!” he said, staggering into the McLintock kitchen and collapsing onto an up-market colander-backed metal chair with a laugh.

Libby sat down on its twin, grinning at him. “Yeah.”

“You’re a tremendous help in a kitchen, Libby!” said Aidan with a smile.

“Me? I just did what I was told,” she said limply.

He rather thought that was the point. No arguments, no telling him how to do it better, and exact following of his instructions—something, in Aidan’s considerable experience of cretins, that only the very intelligent were capable of. “Yes. Like the best sort of theatre sister assisting the surgeon, I think,” he said thoughtfully.

“Bullshit!” replied Libby with a laugh, very flushed and pleased. “Shall we have our lunch now?”

“Yes, of course. Er, well, that was the chicken, I’m afraid! I’ve got a couple of ducks but they’ll take hours to cook… Um, well, the batter for the zucchini flowers will only have improved: the starch will have had time to expand. I did buy some nice fresh free-range eggs—well, omelette aux fines herbes?”

“That sounds yummy,” agreed Libby. “Can I chop stuff?”

“Mm-hm, in a bit,” said Aidan, getting the batter out of the fridge and showing it to her. “See, it’s flowered. Uh, expanded. Don’t tell me this is absurd and over the top, I know it, but the zucchini flowers looked so lovely I couldn’t resist them.”

“No. Tamsin had a recipe for those in a magazine,” said Libby, eyeing the proceedings cautiously. “And I think she said she saw it on TV, too, I think it was that programme on Friday nights. It’s not just cooking, it’s home stuff and gardening stuff. Um, you might not have seen it. But her and Jayne didn’t really fancy eating flowers.”

“No? Well, they’re delicious, you’ll see!” He dished up rapidly. And rescued the white wine from the fridge. “Come on through.”

“Ooh, heck, you’d got everything ready,” discovered Libby, looking in some dismay at the beautifully set table in the awful McLintock dining-room. –Heavy dark teak cabinets, sideboards and dining suite. Expensive Eighties bad taste—yep.

“Of course! Never mind, better late than never, eh? I couldn’t let Livia down: she and Wal were so bloody decent to me when Dad died.”

“Yes. She’s nice, isn’t she?” said Libby, sitting down and smiling at him. “At first you think she’s a bit mad and, um, affected, I think is the word, but she’s really nice underneath it.”

“Exactly! She coped wonderfully with all the hags of legal eagles’ wives that kept ringing up, and she and Andrew between them sorted out all the cards of condolence and the wreaths and drew up a list and he got some thank-you cards printed—dunno if it’s the done thing but there were so many of them we couldn’t have replied by hand—and so we more or less managed to do the thing properly. Though without the huge funeral service that the old bugger would have seen as his due: I’m not that damned hypocritical; and even Candy didn’t suggest it,” he ended on a grim note.

“No,” said Libby sympathetically. “I see.”

Aidan came to, flushing. “Sorry. Taste your zucchini flowers.”

To his relief she seemed to genuinely like them. “Guess what?” he said, holding up the bottle.

“Same as Livia’s?” ventured Libby,

Aidan nodded, his eyes sparkling, and poured the wine as she collapsed in giggles.

As they ate and drank she admired the unusual flower arrangement in the middle of the table, so he explained that it was basically the bunch of herbs that the dear little girl had sold him plus the garlic flower she’d presented him with, with the addition of some sage leaves and tea-tree sprigs from Judge McLintock’s garden.

“A garlic flower?” she said, looking at the mauve-tinted ball. “I couldn’t imagine what it was! Isn’t it miraculous?”

Since this was Aidan’s own secret feeling about the globular flower heads he agreed enthusiastically, topped up her glass and, sitting back at his ease, bored on for ages about his grandmother’s kitchen garden and thence, by a natural progression, her kitchen and her wonderful home cooking…

“Uh, sorry, boring on,” he said, flushing.

“No, it’s interesting. So your grandmother did her own cooking, even though they were rich?”

“Yes. It was the thing in those days even in their income bracket, though she did have a woman to help with the housework. Not a local, don’t think any New Zealand women were doing other people’s housework in the Fifties and Sixties: too busy tied to their own kitchen sinks, mm? No, Mrs Wolf was a German Jew—refugee. Holocaust survivor,” said Aidan, making an awful face. “A terrifically hard worker, didn’t mind what she did. Taking her on was about the only decent thing Grandfather ever did in his life. Well, perhaps it was conscience, or a feeling that there but for the grace of God—dunno. The family was Jewish way back,” he explained. “My great-grandfather emigrated from Prussia in the 1880s.”

“I see. But I thought you said your father’s funeral service was Anglican?”

“Uh-huh. Dunno exactly when they changed, or why: Grandfather never referred to it,” he said with a shrug. “But judging by a Hungarian Jew who used to work for Wal, I’d say it wasn’t just wanting to be accepted by the majority, though there was certainly some anti-Semitism in New Zealand back in the early twentieth century, but fear of the pogroms. Stephen Smith—the Hungarian, dunno what his real name was—always used to put down his religion on the census forms as Roman Catholic as a precaution against persecution. –I’m not kidding,” he added grimly, as Libby gaped at him.

“But—when did he come out here?” she groped.

“When Hungary was overrun by the Russians, I think. He was terrified of Communists as well as Fascists. –Yeah,” he said to her face of dawning horror. “Thank God we were born on this side of the world, eh?”

Libby nodded hard. After a moment she looked with frank interest at his dark hair, long-jawed but basically oval face and slightly beaky nose and said: “I can see it now. I thought perhaps you might have Irish blood.”

“No: Scottish—Mum’s side. And Prussian,” he said drily: “wrong side of the blanket, no doubt. Dad looked like a caricature of a Prussian general: thick straight neck, bullet head, pale skin, fawnish, almost colourless hair, bulgy blue eyes, meaty sort of figure. Bobby and Candy both take after him, poor things, though in Bobby’s case the vegetarianism has taken care of the figure, and the hair hasn’t been allowed to be fawn since he was eighteen!”

“I see,” said Libby with interest. “And what about your grandfather?”

“Sir Cornelius Vine,” said Aidan with a grimace, “was a dead ringer for me, I’m sorry to say. And we’ve got the bloody oil painting to prove it.”

“Help,” she gulped.

“Yeah, that that was the cry of the unfortunate victims that appeared before him in court. Have a bit more wine and then we’ll tackle the omelettes!”

They did that. Libby chopped the herbs to his exact specifications.

“Yum, it’s so creamy,” she said in astonishment, tasting the result. “My omelettes always come out leathery.”

Smirking, Aidan bored on for ages about the right way to make an omelette… “Shit, boring on again!” he discovered. “Shoot me now, get it over with.”

“No. You ought to be a cook,” said Libby, smiling at him.

“Livia’s up-market lady friends would agree with you!”

“No, well, if you’re really fed up with the law like you reckon, why not? Just little lunches and dinner parties, not running a restaurant, I don’t think you’d like that. But home catering for small parties. It wouldn’t bring in a fortune, but you did say that you didn’t need to make money.”

Ouch, had he said that? “Uh—yeah,” said Aidan weakly.

“I suppose being a caterer isn’t fancy enough for a person whose father and grandfather were judges.”

Aidan Cornelius Vine went very red. “Both of them would have thrown ten thousand fits at the very idea, that’s true. Makes it all the more tempting!”

“Good!” said Libby with a smile. “Well, it’s just an idea, Aidan. Your food’s really wonderful. But, um, you might not like the, um, the servile side of it; Jan says you do have to bite your tongue sometime with the clients. Dad usually copes okay, he’s good with people, but sometimes it gets too much for him and he goes off to his shed.”

“Mm—or goes fishing? Like Wal, today: I nearly died when Livia said he’d gone fishing! –Well: ‘gone fishin’, instead of just a-wishin’.’ –No? The song’s been running through my head ever since I laid eyes on the lake! –I’m used to doing the hypocritical thing with clients, don’t think it’d be all that much different!”

“No,” she agreed thoughtfully. “And you could employ someone to do the serving, you could minimise the actual contact with them.”

“Certainly! To do serving and chopping; why don’t you join me in the enterprise, Libby?” said Aidan gaily. He raised his eyebrows at her. “Gitche Gumee Catering? Shining Big-Sea-Water Chefs Incorporated?”

Gratifyingly, Libby collapsed in giggles, shaking her head madly. “No! They’d never get it!” she gasped.

“That or they’d think I was trying to translate a Maori name,” he admitted. “There is a lake with a name just like that.” He got up. “Hope you like raspberries. These are superb; I thought just plain with a little cream? Or yoghurt, if you’d prefer it.”

“Cream, please, though I know it’s fattening.”

Mm, it was that, and on top of the cholesterol in the eggs— Oh, well, once couldn't hurt. Aidan fetched the raspberries and cream, unaware that he was smirking.

Funnily enough once they got to the coffee stage he found there was something much more interesting to do, so, leading her into the horrors of his masculine McLintock bedroom and apologising for it—dark brown, largely, the bed featuring a mountainous padded headboard, untouched by human hand since 1985—he removed the high-heeled white sandals with the entrancing ankle straps round her slim ankles, the coral slacks and the sleeveless white top with its spray of orange blooms, blissfully unaware that Libby had spared the world the blouse that completed Tamsin’s vision of suitable travelling wear for middle-aged ladies, and discovered the lacy coral underwear. Ooh!

… “Thank you,” said Libby very faintly, quite some time later.

Aidan lay on his back gazing blankly at the misguided thing Judge McLintock had stuck in the middle of the bedroom ceiling. “No, thank you.”

“No, I mean, waiting for me,” said Libby in a strangled voice.

Uh—oh. “My pleasure!” he said with a laugh in his voice. “And I can assure you that even if I’d come first I’d have made sure you had a come, too.” He groped for her hand and squeezed it rather hard.

“Mm. Thanks. Only nice men do that.”

Aidan was rather glad to hear he fell into the category! He refrained with a certain effort from asking what other nice men she’d known. None of his business, after all, and, uh, well, lovely as she was—and quite bright, too—did he really want that sort of intimacy at this stage?

They were sitting up sipping drinks—she’d only wanted mineral water, to his amusement—when she said thoughtfully: “Actually, doing catering might not be right for you. A person with very high standards doesn’t usually like having to compromise them.”

Had he been seriously considering catering, anyway? “Oh?” said Aidan languidly.

“Mm. See, Jan’s discovered that most of their clients don’t want her really good food. They don’t know what it is. I mean, take that rabbit the other night. Even the two gourmets from Auckland didn’t think it should have been wild rabbit. I mean, they praised it to me, but they really meant it, they weren’t just being polite, because I heard them talking about it when I was serving someone else. The thinner one, Tony, he was wondering if he could do it and deciding he’d ask Jan for the recipe.”

“If they were such gourmets, I’d have expected him to know exactly where to go for the recipe: it’s an Elizabeth David classic,” replied Aidan drily.

“That’s my point. They’re the top end of the market and they didn’t know what was wrong with it. Though I suppose you can’t blame them for not having had wild rabbit, it’s only people like Dad, that get out and shoot it for themselves or that can remember back to the Forties when you could buy it from the butcher, that have ever had it.”

“Uh—could you buy it from the butcher?” replied Aidan limply.

“Yes, Jan remembers her mum doing rabbit when she was very little. She used to give her a kidney for a treat,” said Libby, smiling. “They just lived in an ordinary suburb.”

“Mm. Can you give me another example of Jan compromising her standards, perhaps?”

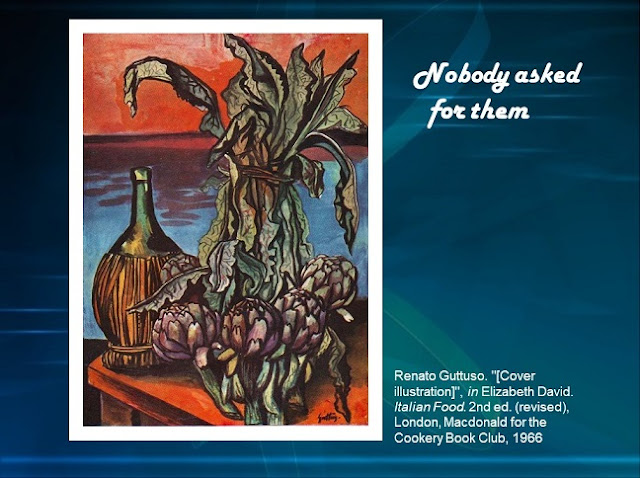

“Um, heck, I’m not a gourmet, Aidan!” replied Libby with a laugh. “Well, the lunches, I suppose. She usually just does ordinary things, like potato salad, unless someone’s booked for something special. And, um, well, she’s given up putting artichokes on the menu: whole ones, I mean, because nobody asked for them. Taupo Organic Produce often give her some when their artichokes have gone berserk, but her and Dad usually have them themselves, or them and their friends Polly and Jake when they’re staying when them.”

“I never saw any artichokes at Taupo Organic Produce!” he said crossly.

Libby blinked. “Um, they probably sent the last lot up to Auckland.”

“Then there must be somebody in the country who eats them!”

“Yes, but they’d be a very small proportion of the population as a whole,” she said seriously.

He frowned. “I see. Jan hasn’t considered that if she offers excellent food she may contribute to raising standards?”

“Yes, but that’s what I’m trying to say: it didn’t work, ’cos nobody ordered the stuff. And, um, she said that most people that can afford to pay for the best don’t want food that’s simple but good, these days, they want silly little piles of mucked-around stuff that the cook’s had his fingers in for hours,” said Libby, swallowing, “sitting in swirls with dots of olive oil on the plate going to waste. And before you start, I saw that programme about that Italian man on the Murray that you and your friends were going on about the other night, and even he was serving his meals in little piles!”

“Uh—not all of them,” said Aidan limply. “I suppose that’s his compromise. But his food is really excellent.”

“Yes, but the population’s miles bigger and there’s more foreign influences from all the immigrants. The whole of New Zealand’s population is about the size of Sydney’s. And, um, you have to admit, Aidan, that man’s really worked at it, hasn’t he? And he’s very good at, um, advertising himself. I mean, you wouldn’t want to go on TV, would you?”

Aidan winced. “No.”

“No, you haven’t got that temperament. But you could see that he was really enjoying it, he must have a very extroverted personality.”

“Right, a born self-promoter,” he said with a sigh.

“Mm.”

“It is possible to get excellent ingredients here, someone must eat them!” he said crossly.

“Yes. Jan was telling me that there are little restaurants that do very well with high-class ingredients and good food, but on a very small scale, and they’re usually within relatively easy reach of the big cities. And, um, very often they’re run by the sort of people that run the B&Bs back home. Semi-retired people that have already succeeded at another profession.”

“Uh-huh. Do you always set a bloke up only to knock him down again?” he said crossly.

“I—I duh-don’t think so!” stuttered Libby, very taken aback. “I was only trying to discuss it seriously.”

Aidan gnawed on his lip. “Yeah. Sorry.” He got out of bed. “I think I’ll make that coffee. Want some? There are some delicious little crescent biscuits that Candy made, too, they’d hit the spot.”

“Mm, that’d be nice. Thanks,” said Libby in a squashed voice.

To his relief she didn’t bring up the topic of catering again. Well, at least she wasn’t a nagger, like some. No, Hell, like most!

“What about trying for lunch again tomorrow? This time without Livia and Co.!” he said with a smile.

“I can’t tomorrow, I’ve got to take some of the clients down the Rewarewa Trail. It’s only a five-K bush walk, but some of them don’t feel confident enough on their own.”

Aidan sighed. “You’re doing this trail guiding at lunchtime, are you?”

“Yes, ’cos Jan said they could have a picnic lunch if they liked and they decided they would.”

“Isn’t there anyone else that can do it?”

“No, Sean’s guiding the long trail tomorrow and Jayne’ll be waiting in the restaurant.”

“Your niece?”

Libby smiled a little. “She’s out on the lake every day with her boyfriend helping him take water samples. It’s for his Ph.D.”

“Right. Then the day after?”

“No, I’m helping guide Vern Reilly’s minibus tour of National Park.”

“Didn’t you just do that the other day?” he said in an annoyed voice.

“Yes, but this is another lot, Aidan,” replied Libby seriously. “He does a tour every few days in summer.”

“Can you name a day, perhaps?” he said with a sigh.

“Um, well, not really,” she said apologetically, “because the ones that want a guided bush walk usually only ask a day in advance.”

“Then I suppose I’ll have to take pot luck. Ring you as and when. And I won’t ask how Jan and Pete managed when they didn’t have you and your sister on tap!”

“Only just, I think. They—they’ve had student helpers and, um, some of their friends’ kids, off and on.”

Aidan didn’t register that she was sounding squashed again, he was feeling too cross himself to notice anything, much.

“Um, sorry, Aidan, I’ll have to go. I’ll have to get changed and then get across the lake, I’m helping with the waiting this evening.”

“Uh—yes, of course. Use the ensuite, if you can bear the fifteen hundredweight of khaki slate in there. –Indian, I think, bloody Paulette did one of our bathrooms out in it at one stage and then decided she hated it.”

“Um, thanks,” said Libby faintly, ignoring the reference to his ex-wife because she had no idea how to respond to it.

She vanished into the ensuite. Aidan frowned and absent-mindedly took the last little crescent biscuit.

Possibly the final circumstance which made him look again at the idea of doing some sort of catering was Libby’s pouring cold water on the notion. Opposition had always spurred Aidan on: he’d probably never have gone to Australia at all, never mind the genuine impulse to escape the path to the New Zealand bench laid out for him by Sir Simon and Sir Cornelius before him, if his father hadn’t rubbished the whole idea, which he’d floated less than half seriously, of company law and Sydney anything.

The final factor was the phone call the next morning, shortly after Andrew had mooted the idea of thermal baths, to which bloody Caroline had responded all too eagerly, from Livia’s friend Joan Whatsername—Joan Hutchins, right—who must have wheedled his number out of Livia. Couldn’t he possibly? Just an intimate dinner for three couples! She realised he was on holiday and normally worked in Sydney for a high-class clientele—Aidan blinked, had Livia told her that?—but of course she’d be only too glad to pay his normal fee! He was very tempted to refuse just to see how far she’d up the ante, but she was adding eagerly that naturally he’d have free rein with the menu, that was quite understood! Livia had presumably told her that, too. Coincidentally it was the very night that Don had proposed booking a table at Fern Gully Ecolodge’s restaurant—silly little piles of mucked-around stuff that the cook had had his fingers in for hours, quite. Okay then, why the Hell not? It’d be fun! And God knew there was nobody in these parts who’d recognise A.C. Vine, Q.C., from Sydney.

Next chapter:

https://summerseason-anovel.blogspot.com/2022/09/sage-counsel.html

No comments:

Post a Comment